|

|

||||||||

|

Apr 10, 2025 - [TOS] TOS Season 3 Screencaps: Remastered Visual Effects Apr 09, 2025 - [HOME] Nichelle Nichols Space Camp to Launch in January 2026 Apr 09, 2025 - [PRO] PRODIGY Season 2 Screencaps: "Ouroboros, Part II" Apr 07, 2025 - [PRO] PRODIGY Season 2 Screencaps: "Ouroboros, Part I" Apr 07, 2025 - [HOME] WeeklyTrek: STRANGE NEW WORLDS Season 3 Teaser Arrives Apr 05, 2025 - [LOW] LOWER DECKS S4 Screencaps: "Old Friends, New Planets" Apr 03, 2025 - [HOME] Preview: TREK Food & Drink Menu at Universal Fan Fest Nights Apr 02, 2025 - [HOME] Nacelle Announces International Availability for TREK Figures Apr 02, 2025 - [SNW] Watch the STRANGE NEW WORLDS Season 3 Teaser Trailer! Mar 30, 2025 - [HOME] Nacelle Reveals Wave 2 STAR TREK Action Figure Lineup Mar 30, 2025 - [PRO] PRODIGY Season 2 Screencaps: "Touch of Grey" Mar 30, 2025 - [PRO] PRODIGY Season 2 Screencaps: "Brink" Mar 29, 2025 - [HOME] Master Replicas, Hiya Toys Launch New STAR TREK Preorders Mar 29, 2025 - [LOW] LOWER DECKS Season 5 on Blu-ray: Review & Giveaway Mar 28, 2025 - [TOS] Wand Company Tricorder Replica Pricing, Fulfillment Plan Revealed Mar 27, 2025 - [DSC] DISCOVERY Season 5 Screencaps: "Life, Itself" Mar 24, 2025 - [TOS] TOS Season 2 Screencaps: Remastered Visual Effects Mar 23, 2025 - [HOME] IDW Unveils Three STAR TREK Comic Miniseries for 2025 Mar 23, 2025 - [TOS] Master Replicas Offers Full-Sized Original Enterprise Plaque Mar 21, 2025 - [PRO] PRODIGY 214 Blu-ray Screencaps: "Ascension, Part I" Mar 21, 2025 - [PRO] PRODIGY 215 Blu-ray Screencaps: "Ascension, Part II" Mar 19, 2025 - [DS9] Video Update: "DS9" Interviews & Behind-the-Scenes Mar 18, 2025 - [LOW] LOWER DECKS S4 Screencaps: "The Inner Fight" Mar 17, 2025 - [DSC] DISCOVERY Season 5 Screencaps: "Lagrange Point" Mar 16, 2025 - [HOME] WeeklyTrek: STRANGE NEW WORLDS Starts Season 4 Filming Mar 15, 2025 - [TOS] TOS Season 1 Screencaps: Remastered Visual Effects Mar 14, 2025 - [TOS] Master Replicas Recreates Original STAR TREK Coffee Cup Mar 14, 2025 - [HOME] Fundraiser Success - Thanks to You! Mar 14, 2025 - [DS9] "Star Trek: Deep Space Nine" Episode Trailers — Season 7 Mar 13, 2025 - [PRO] PRODIGY 213 Blu-ray Screencaps: "Cracked Mirror" |

|

||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

ST Online:

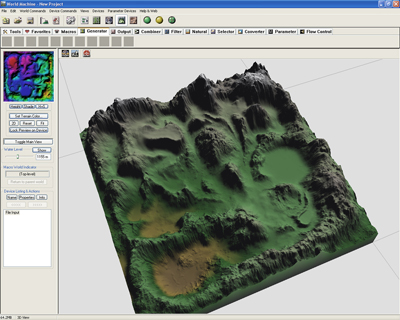

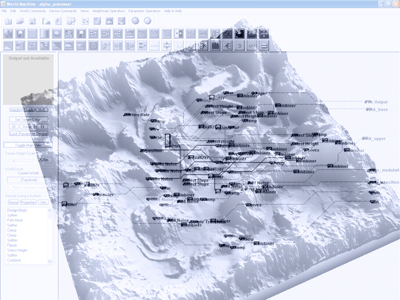

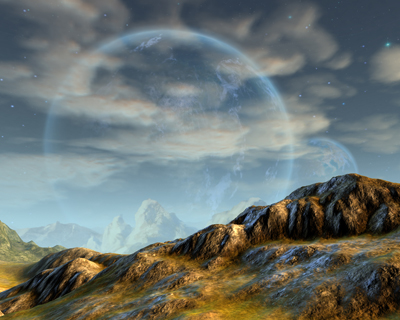

Designer Diary : Creating Environments |

|

||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

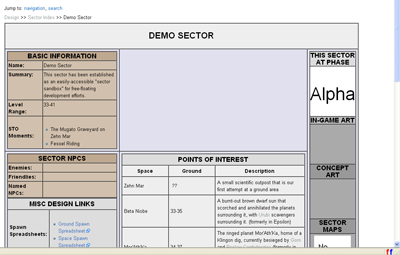

TREKCORE > GAMING > ST ONLINE > DESIGNER DIARY > Creating Environments

PUBLISHED: July 14, 2007 This was originally published on the official Star Trek Online website. Entry 1.0 - Hailing

Frequencies Open Welcome to the first edition of the STO DevLog, a

periodic behind-the-scenes look into the development of Perpetual

Entertainment's Star Trek Online. During the months before we're ready

to roll out STO in a big, BIG way, we hope you'll make the DevLog the

place to go for informative, entertaining, and intriguing peeks into

the making of the most ambitious Star Trek game in the history of the

galaxy.

Pretty cool, eh wot? It reminds me a bit of a quote from Wrath of Khan:

We're not down to the six minute mark yet, but we're

getting there.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

All STAR TREK images, trademarks and logos are owned by CBS Studios Inc. and/or Paramount Pictures.

All original TrekCore.com content (c) 2025 Trapezoid Media, LLC. - Terms & Conditions