|

|

|

TREKCORE >

GAMING >

ST ONLINE >

DESIGNER DIARY > Creating Environments

PUBLISHED: July 14, 2007

AUTHOR:

Mike Stemmles

This was originally published on the official Star

Trek Online website. Entry 1.0 - Hailing

Frequencies Open

(a.k.a. "The Coolest Thing")

Stardate 60998.6 (July 14, 2007)

Welcome to the first edition of the STO DevLog, a

periodic behind-the-scenes look into the development of Perpetual

Entertainment's Star Trek Online. During the months before we're ready

to roll out STO in a big, BIG way, we hope you'll make the DevLog the

place to go for informative, entertaining, and intriguing peeks into

the making of the most ambitious Star Trek game in the history of the

galaxy.

I'm your host and STO Story Lead, Mike Stemmle. I'm also, as my

friends, family, and coworkers can attest, an unabashedly rabid

Trekkie. How rabid? Let's just say that music from Star Trek: The

Motion Picture was played during my wedding ceremony and leave it at

that, okay?

As a big ol' Star Trek fan, you'd think that the coolest part of my

job is working with Gene Roddenberry's fabulous creations. And make no

mistake, wiling away one's days adding to the legends of Kirk, Picard,

and Sisko (among hundreds of others) is an exceptionally spiffy way to

make a living.

But it's not the coolest thing.

The coolest thing about working on a project like Star Trek Online is

the host of unexpected little surprises that emerge as the game takes

shape. Because STO is such a large undertaking ("massive," even), it's

pert-near impossible to keep one's eyes focused on every single aspect

of its development at all times. A fortuitous consequence of this

phenomenon is that sometimes I don't get a look at a lot of the really

keen stuff going on in the game until it's nearly fully-formed.

Exhibit A: Recently, I was absolutely floored by a demonstration of

how we'll be crafting our exotic alien environments. For years, the

process of constructing believable landscapes (alien or otherwise) has

been a grueling, painful endeavor. But these days technological

advances have come along to help designers and "world builders"

rapidly assemble huge environments that look like they were shaped by

natural forces, while simultaneously providing all the necessary

gameplay "Points of Interest" laid out by the design team. Here's how

it more or less works:

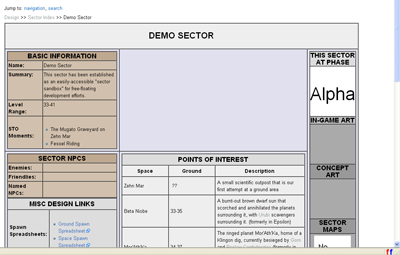

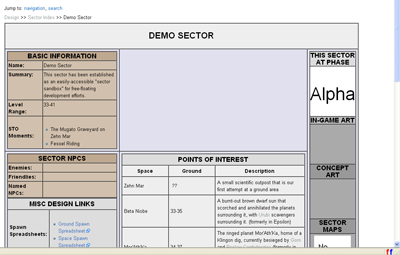

- World and story designers talk for a long time

about what they want to do on a planet. This is a mysterious process

that involves french fries, meetings, and much frozen yogurt. It

eventually produces a somewhat drab (but very informative) wiki page

like this:

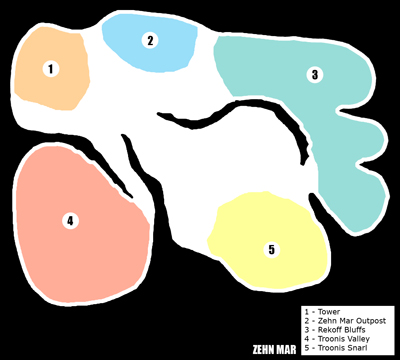

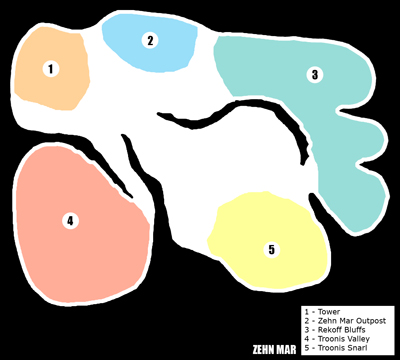

- Taking cues from the wiki page, a world designer

creates a rough 2D map of a planet's layout, which highlights the

dangerous areas, the safe paths, the significant

structures/towns/cities, and anything else an artist might need to

know. These first maps tend to be both colorful and crude:

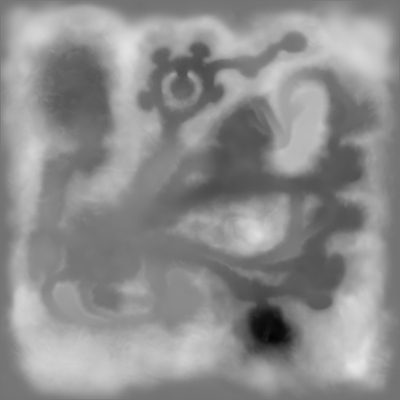

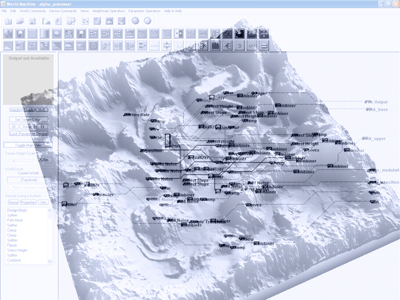

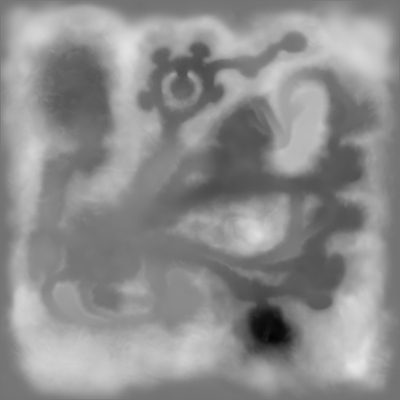

- A world artist takes the designer's 2D sketch and

uses it to quickly create "height maps" of the landscape, which are

more than a little bit eerie and foggy:

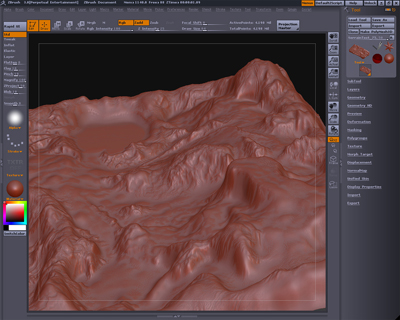

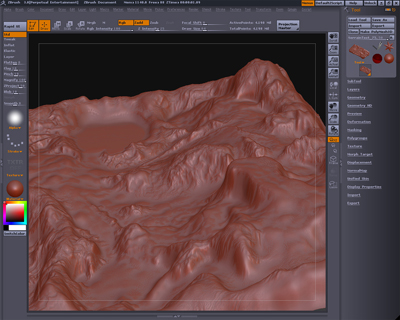

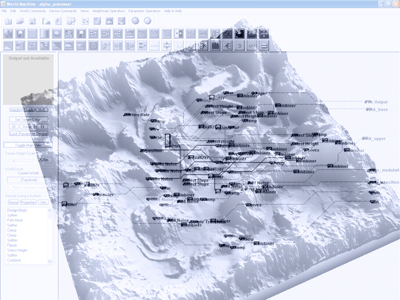

- The world artist takes this height map, and uses

it to extrude a rough 3D layout of the area. The resulting map looks

remarkably like it was carved out of a block of strawberry ice

cream.

- The world artist and world designer pore over ice

cream map, iterating on it until they're happy with the overall

shape of the world.

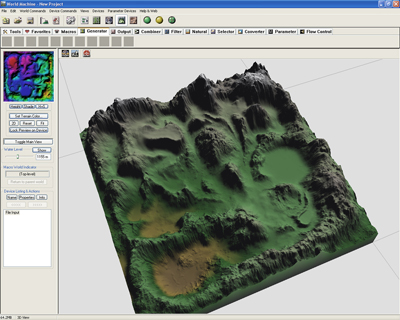

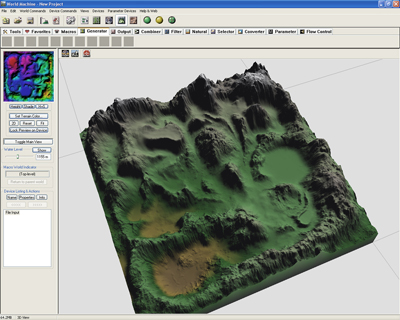

- The now-finished height map is fed into World

Machine, an intensely insane piece of software that generates

realistic landscapes using height maps and user-configurable "rule

sets." These rule sets govern things like "Rocks on this planet are

powdery" or "Mountains on this planet are 90% eroded" or "Streams in

this area are stagnant." By carefully configuring these rules, our

artists can swiftly create an absurd range of environments, from the

striking deserts of Vulcan to the sodden swamps of Ferenginar, to

everything in between and beyond:

- Once all the rules are in place, World Machine

procedurally applies them to the height map (among other inputs),

and begins to generate a landscape. Thanks to our artists' suite of

recently-purchased 64-bit machines, this process only takes about 20

minutes, giving our artists just enough time to

squeeze in a

quick round of Guitar Hero II check their company email.

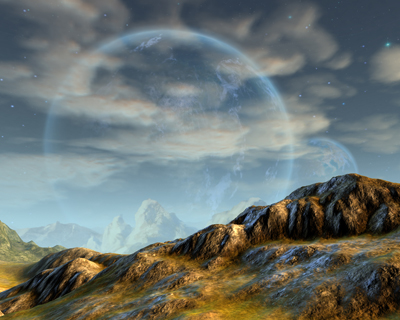

- When the World Machine is finished, an amazingly

detailed in-game landscape pops out, ready to be populated with

surly Klingons, giant radiation towers, and maybe even a tribble or

three. Thanks to the blazing speed of World Machine, any major

changes we need to make to the landscape at this point can easily be

made in less than a half-hour. Just to wet your whistles, here's a

small tease of a typical in-engine terrain generated by the World

Machine:

Pretty cool, eh wot? It reminds me a bit of a quote

from Wrath of Khan:

DOCTOR MCCOY: According to myth, the Earth was

created in 6 days. Now, watch out, here comes Genesis! We'll do it

for you in 6 minutes!

We're not down to the six minute mark yet, but we're

getting there.

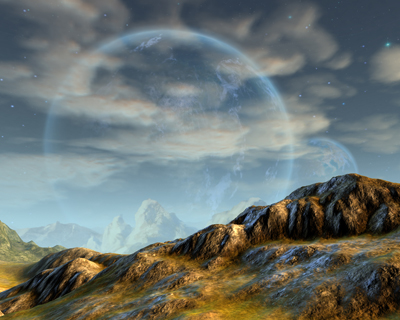

Join us again next time on the DevLog, when we'll have some more

interesting looks into the Star Trek Online development experience. But

before we go, here's a completely random, utterly cool "Star Trek Online

Image of the Moment," brought to you by concept artist extraordinaire

Rob Brown:

Gosh.

Jolan True,

Mike Stemmle, Emergency Story Hologram

PS Special thanks to Adam Murguia, Dan Fuller, and Greg Faillace for

their help with the imagery and tech clarifications.

Mike Stemmle is the Story Lead on Star Trek Online. He has spent much

of the past two years deep in the plak tow.

|